The Cirrus Project

- Francesco Lena

- Jun 19, 2025

- 5 min read

Those who know me well know that the name "Cirrus" follows me in several projects. But perhaps few remember where it all started. Well, I'll try to tell you a little about where it all came from.

I was born and raised in a small town in the interior of São Paulo. Not extremely bucolic, very close to the metropolis of Campinas, but small enough to have some unique characteristics. One of them was my school - Tema - which, during my time there between elementary school II and high school, greatly shaped my tastes and defined many of my own things that I carry with me to this day. From personal interests to professional ones.

I would say that Tema was different from many schools, including those in Amparo, mainly because of the friendly and close relationships between teachers and students. I imagine part of this was due to the small classes. In my high school, classes never exceeded 20 people. But part of it was due to the innate interest of the founders - also teachers - which was also reflected in the rest of the faculty. I can't say for sure about today, but I hope it stays the same.

These friendships led to mini adventures. Trips, camping trips, science fairs, and strange ideas that worked. In one of them, with my friend and physics teacher Bruno, we started thinking about projects to do with the class that weren't as cliché as the volcano at the science fair. And, I don't remember exactly what the context was, we ended up wondering how high helium balloons (birthday balloons, really) go when they're lost.

As a good physics teacher, Bruno created hypotheses and calculations. It didn't seem like anything exciting. But, in the research and estimates, we came across something we didn't know about. Weather balloons. Exactly the same thing, only made to go as high as possible, carrying instruments that measure atmospheric parameters as they ascend, the basis for modern meteorology.

It may seem strange that in high school we had never heard of such a common technology. But I believe that you only came into contact with the term through an idea that became popular: tying a GoPro to a balloon and filming its ascent to the stratosphere - the next layer. And that's what we found next. A somewhat different video, of a GoPro on a weather balloon launched during a solar eclipse.

We were immediately hooked on the idea. There was almost nothing about it on the internet. A few other videos, a blog, but nothing went viral. I don't think the term even existed yet. It was 2012. Today there are thousands of videos of similar feats, but at the time it was new. And there were no similar videos in Brazil.

We decided we were going to do this. We tried to figure out what we needed. A balloon, four or five cubic meters of helium, a Styrofoam box, of course, a GoPro-type camera. And to find the camera? Some kind of tracker. Maybe more batteries. A datalogger? And a parachute! The list of materials soon became too expensive for a teenager and a teacher just starting out in his career. But the school helped. A small sponsorship here, another here, a raffle later, and we had enough money to buy the equipment.

Along with the money came the curiosity of those who helped. Many friends got on board with the idea. So did my father, who always admired everything that came out of the ground. Soon we had a mini team, materials, some studies, and we could get started.

Within a few months, we had purchased and received the equipment. It was housed in a very low-tech Styrofoam box. There was no engineering involved, just the best effort to ensure that the equipment would not freeze. To track the so-called "probe", a Spot Gen2 tracker, a small satellite device, was used. A GoPro II and a few more pieces of equipment later, the probe was ready for its journey.

The launch window was defined with a very interesting tool developed by a group of students and hobbyists, CUSF ( https://predict.sondehub.org/ ). This tool uses wind speed and direction forecasts from the GFS (Global Forecast System) model in different atmospheric layers to predict the balloon's drift and approximate the landing site. In this case, the date chosen is to look for an uninhabited location, and as close to the launch site as possible.

The event took place on a sunny Saturday at the Amparo model airplane track. Around a hundred people attended the event. Several students from the school and other enthusiasts from the city had heard about the project from the local newspaper. There was practically no wind, which made the balloon rise almost straight up. With the gradual reduction in atmospheric pressure - to up to 1% of that at sea level, at its peak - the gas inside expands, until the latex balloon can no longer withstand such tension and bursts, ending the flight.

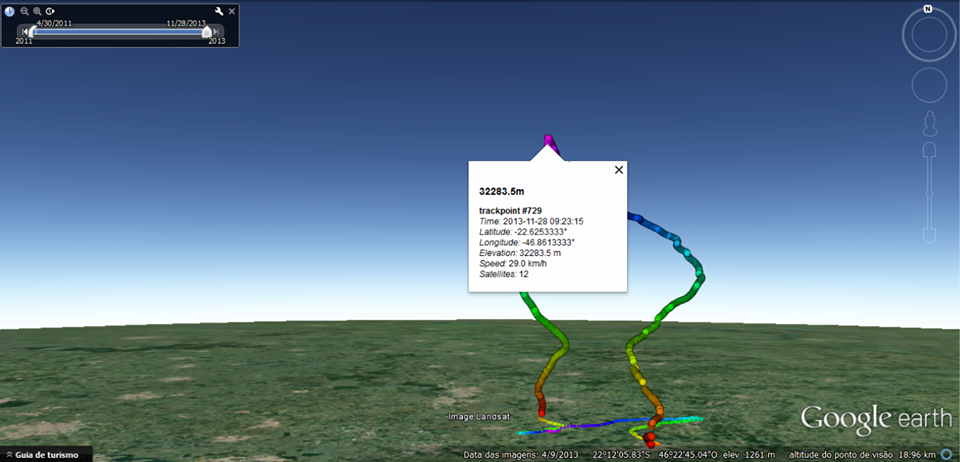

As the ascent was above us, it was possible to see the balloon until it burst at an altitude of over 32 km, when it disappeared. And then the rescue began. We set off in several cars towards the point predicted by CUSF for the fall. We were without coordinates for a while because SPOT had a maximum altitude limit of 9 km, if I'm not mistaken.

The fall is rapid, even with the parachute, since the air density is a fraction for much of the descent. The terminal velocity exceeds hundreds of meters per second for a brief period. When it gets close to the ground, it is reduced to about 5 m/s, preventing the probe from being destroyed on impact.

The "landing" was on a cassava plantation in a nearby town. 19km from the launch site - incredibly short when compared with the ascent of over 32km, passing through layers of jet streams. The datalogger, with a GPS not limited to altitude, recorded the entire flight profile.

During the rescue, we removed the memory card from the GoPro to check what was recorded. The Styrofoam box and the additional power bank worked, powering the camera that recorded the entire flight. We advanced to the middle of the video - and were impressed. Seeing the immensity of the beginning of space, and the fragile surface of our planet, on a horizon that, at an altitude of 32 km, extends for more than 600 km, was a unique experience. Amparo is about two hours from greater São Paulo, and a little over three from the coast. But at this altitude, with especially good weather, it was possible to record images of the entire metropolis, and kilometers out to sea.

The feeling of accomplishing something that previously seemed unattainable was unique. Especially for high school students, whose routine, full of discussions about college entrance exams and fear of the new, set their limits much lower than the sky. It took months of planning and work by many people. The result, although much more artistic than scientific, inspired a group of students. Unintentionally, it also opened doors for me. I will tell you more about this in other posts.

Comments